Our Library - Articles

Музыкально-компьютерные технологии как информационно-трансляционная система в Школе цифрового века

Музыкально-компьютерные технологии как информационно-трансляционная система в Школе цифрового века

УДК 781.1 Горбунова И.Б., Заливадный М.С., Хайнер Е.

Музыкально-компьютерные технологии как информационно-трансляционная система в Школе цифрового века

Музыка является одной из граней постижения духовной содержательности мира, его красоты, находящей отражение в звучании. Звучание музыки воспринимается человеком как особое информационное пространство.

Аудиальность восприятия музыкальной ткани связана с живым, непосредственным опытом человека, основанном на временнóй природе слухового переживания. Такое восприятие один из видных учёных современности - Г.М. Маклюэн назвал «горячим», непосредственным в отличие от зрительного опыта, несущего в себе, по его словам, возможность «отстранения», «холодности», размышления и оценки, подчеркивая, что зрительный опыт дает возможность для спокойного, не обусловленного живым течением музыкальной ткани анализа видимого мира с помощью возможности тождества и различия построений, созерцаемых на некотором расстоянии [27].

Появление и развитие музыкальной письменности и, в особенности, нотопечатания как инфомационно-трансляционной системы внесло неоценимый вклад в аналитический способ представления о музыкальном языке. Точная нотная запись не только позволила услышать и прочувствовать музыкальное полотно с помощью зрительного восприятия музыкального текста, но и понять (соответственно – осмыслить) архитектурные особенности музыкального материала, творчески перерабатывать его вне зоны «живого», аудиального восприятия без привязки к «горячему» восприятию. Продолжая мысль Маклюэна, можно отметить, что возможность как «горячего» переживания, так и «холодной» оценки музыкального произведения способствует развитию восприятия звучащего музыкального произведения: от личностного, непосредственного – к критическому, осмысленному.

Возможность тиражирования нотных текстов способствовала интенсивному развитию музыкального языка, а двуполярность его восприятия вывела музыкальную культуру на уровень высшей степени абстрактности, выделив ее в особенный вид передачи информации. «Если мы будем говорить о визуальном опыте, то он позволяет нам совместить одновременно два или больше объектов, и не просто совместить, но сравнить Что касается слухового опыта, то тут такой возможности нет. Мы можем сравнивать только объекты, находящиеся во времени» [28].

Нотописание, которое, являясь в большинстве распространенных его форм (в том числе — традиционной новоевропейской нотации) выражением изобразительно-знакового представления о музыке, представляет наиболее общие с точки зрения закономерности соотношения между знаками и объектами способы отображения информации о

музыке и выражает важное следствие логико-математического осмысления закономерностей музыки.

Становление и эволюция системы музыкальной нотации происходили параллельно с развитием и теоретическим обобщением закономерностей музыкальной логики, развитием музыкального инструментария [33 и др.]. В ходе этого развития фактически происходила эволюция визуального способа отображения информации о музыке.

Отметим, что логические закономерности строения музыкальных произведений стали предметом целенаправленного изучения музыкантов, начиная с середины ХIХ века (в теоретических работах этого времени обнаруживаются элементы теории множеств). Фундаментальные идеи, составившие теоретическую основу данных исследований, представлены рядом значительных работ (см., например: MarxA. B. DieLehrevondermusikalischenKomposition. Bd. 1–4. Berlin, 1837–1847; RiemannH. GrundriЯ derKompositionslehre. Leipzig, 1897; Лосев А. Ф. Музыка как предмет логики (1927); Эйзенштейн С.М. Вертикальный монтаж // Эйзенштейн С.М. Избр. произв. в 6 т. Т. 2. М.: Искусство, 1964; Зарипов Р.Х. Кибернетика и музыка. М.: Наука, 1971; Xenakis I. Musiques formelles // La Revue musicale, № 253/254. Paris, 1963; Xenakis I. Formalized Music. Thought and Mathematics in Music. StuyvesantandHillsdale, N. Y.: PendragonPress, 1992, и др. Подробный анализ рассматриваемой проблемы приведён нами в работах [6; 13; 14]).

Ранее близкая к понятию информации («субъективно воспринимаемого разнообразия») характеристика «приятности» созвучий выдвигалась в книге Л.Эйлера «Опыт новой теории музыки, ясно изложенной в соответствии с непреложными принципами гармонии» [30] (подробнее рассмотрено нами в работах [17; 18]).

Результаты использования математических методов в музыкознании в первой половине ХХ века получили дальнейший импульс благодаря теории нечётких множеств. Предпосылки для применения этой теории в музыкальной сфере выявились в ходе дальнейшего развития музыкознания и самóй музыкальной практики. Так, в середине XX в. музыкознанием и смежными науками был предложен ряд перспективных идей, содержащих широкие возможности для изучения факторов неопределенности в системе музыкального мышления. В начале 50-х гг. музыкант-теоретик (и учёный-акустик) Н.А. Гарбузов предложил теорию зонной природы музыкального слуха, охватывающую все основные свойства звука. В это же время группой американских композиторов (Дж. Кейдж, Э. Браун, Д. Тюдор и др.) были введены факторы неопределенности в логическую структуру музыки, в дальнейшем интерполированные в технике письма алеаторической и сонористической музыки, получившей широкое распространение во всем мире (См., например: Денисов Э. В. Стабильные и мобильные элементы музыкальной формы и их взаимодействие // Денисов Э. В. Современная музыка и проблемы эволюции композиторской техники. М.: Сов. композитор, 1986. С. 112 – 136; Когоутек Ц. Техника композиции в музыке XX века. М.: Музыка, 1976; Nordwall T. Krzysztof Penderecki – studium notacji i instrumentacji // Res facta 2. Kraków: PWM, 1968. S. 79 – 112.; подробнее изложено в [16; 19 и др.]).

Творческие опыты по реализации этих предложений выявили элементы логической неопределенности, присутствующие в самóй музыкальной традиции, - например, партии ударных инструментов с неопределенной высотой звука, мелизматика, артикуляция, традиционная система динамических оттенков (подробно рассмотрено работах [16; 22; 23]).

К 50-м годам XX в. относятся исследования закономерностей слухо-зрительных синестезий и формирование метода «семантического дифференциала» Ч. Осгуда и его соавторов [31]. Этот метод является важным шагом на пути изучения музыкальных синестезий благодаря их группировке на основе ступенчатых шкал различий, допуская элемент неопределенности в структуре самих шкал, что позволяет говорить о зонной природе музыкальных синестезий. Такой подход придавал шкалам синестетических значений элементов музыки сходство с существующими в музыкальной теории шкалами различий самих этих элементов (простой пример – высотный звукоряд), также допускающими различные степени точности и, соответственно, колебания в расстояниях между отдельными элементами (например, шкала интервалов в работе С. Танеева «Подвижной контрапункт строгого письма» [29]). Оригинальный вариант методики изучения синестетических закономерностей музыки на этой основе (с разомкнутой внутренней структурой шкал и качественным различием самих элементов синестетических соответствий) был предложен Б. Галеевым применительно к изучению слухо-зрительных синестезий. Данные методы и подходы составили предпосылки к применению аппарата нечетких и «грубых» множеств (Заде Л. А. Понятие лингвистической переменной и ее применение к принятию приближенных решений. М.: Мир, 1977; Soft Computing. Third International Workshop on Rough Sets and Soft Computing. San Diego, CA (USA), 1995.), а также теории вероятностей и математической статистики в музыкально-научных исследованиях. Э. Курт и Дж. Шиллингер исследовали более сложные формы, выявляя закономерности пространственно-слуховых синестезий в мелодическом движении и обозначая отдельные звуки мелодии как точки, выражающие моменты смены направлений движения («границы отдельных фаз», «высшие точки линейных кривых») [26; 32]. Шиллингер указывает также на зависимость характера линий во входящих в музыкальные синестезии зрительных представлениях от артикуляции звуков (кривая линия – legato, ломаная линия – nonlegato, точечная структура – staccato).

Рассмотренные теоретические идеи и обобщения представляют также основы исследований различных составляющих системы музыкального мышления, включая ее синестетическую область (подробнее данный аспект рассматриваемой проблемы проанализирован нами в работе []). Данный аспект важен при моделировании синестезий как частного случая виртуальных реальностей средствами информационных технологий и тем самым – использования возможностей музыки в качестве источника таких реальностей [25]. Идея непосредственного включения зрительного ряда в музыку с помощью компьютерных средств приобретает существенное значение не только для синтетических форм художественной деятельности с участием музыки, но и для самогó музыкального искусства [6; 16; 19]. Математически оказалось возможным выразить основные функционально-логические принципы музыки, в частности, положенные в основу создания музыкальных инструментов в различные периоды времени, когда появилась теория множеств, теория вероятностей, и затем и теория нечётких множеств, затем — теория групп (подробнее в работах [4; 17; 19; 20]). Отметим, что все эти закономерности уже находят выражение в творчестве отдельных композиторов, а также в современном программном и аппаратном обеспечении профессиональной деятельности музыкантов [2; 4; 7].

Как функционируют информационные технологии в звуковом, (и — шире — семантическом) пространстве музыки — этот вопрос стал теперь предметом внимания музыкантов-педагогов, представителей других специальностей в связи с формированием новых творческих перспектив деятельности музыканта [1; 2; 3; 5 и др.].

На рубеже ХХ и ХХI веков возникло новое направление в музыкальном творчестве и музыкальной педагогике, обусловленное быстрым развитием информационных технологий и электронных музыкальных инструментов (от простейших синтезаторов до мощных музыкальных компьютеров), новая междисциплинарная сфера профессиональной деятельности, связанная с созданием и применением специализированных музыкальных программно-аппаратных средств, требующая знаний и умений как в музыкальной сфере, так и в области информатики — музыкально-компьютерные технологии (далее — МКТ) [8; 11; 12 ]. Данное понятие (в том или ином варианте его оформления) используется специалистами в различных музыкальных областях с начала ХХI в.

Во многих учебных заведениях мира музыкантам преподаются элементы МКТ (Институт исследований и координации акустики и музыки (IRCAM) при Центре имени Ж. Помпиду в Париже; Центр компьютерных исследований музыки и акустики (CCRMA) Стенфордского университета; Центр музыкального эксперимента Калифорнийского университета в Сан-Диего; Научно-учебный центр МКТ (до 2006 г. — Вычислительный центр) Московской государственной консерватории им. П. И. Чайковского и др.); элементы музыкального программирования преподаются музыкантам в UniversityofHertfordshire, TheUniversityofSalford, AccesstoMusicLtd., BedfordCollege в Великобритании; InstitutfürMusikundAkustik (ZentrumfürKunstundMedientechnologie) в Германии; в филиалах UniversityofCalifornia, StanfordUniversity, NewYorkUniversity, FullSailUniversity (Флорида) в США и др.

О том, что можно представить визуальную информацию о музыке (новые формы нотной записи) с помощью музыкального компьютера [4; 7], свидетельствует тот факт, что, фактически, все предшествующие элементы передачи «языка музыки» — нотных знаков — в той или иной степени присутствуют в новой форме (эволюция визуального отображения информации о музыке воплотилась на современном ее этапе в следующих пяти основных видах нотации):

1) волновая («эволюция звукового давления»);

2) спектральная;

3) «клавиатурный свиток» (Piano Roll);

4) список событий (Event List);

5) традиционный нотный стан (Staff).

Так, например, в некоторых программах (Cubase и других), вместо привычного нотоносца используется сетка, а вместо нот композитор рисует прямоугольники, соответствующие той или иной длительности. Отметим, что и ранее композиторы пытались преобразить универсальную письменную систему записи музыкального языка, и их нотация могла напоминать технический рисунок на шкале времени, или отпечаток снимка осциллографа, запись на ленте электрокардиограммы или какой-либо иной графический способ фиксации музыкальной композиции.

В МКТ объединяются системы точечной, невменной и буквенной нотации, и, в ряде случаев, добавляется числовой способ фиксации характеристик музыкального звука. В значительной мере именно эти данные представляют основу точного исследования различных составляющих системы музыкального мышления, как отмечалось ранее, включая ее синестетическую область [25]. Непосредственное включение зрительного ряда в создание художественного образа и соответствующей музыкальной картины (см., например, исследование В.С. Ульянича «Компьютерная музыка и освоение новой художественно-выразительной среды в музыкальном искусстве») становится актуальным не только для синтетических форм художественной деятельности с участием музыки, но и для самогó музыкального искусства, и, соответственно, системы музыкального образования как профессионального, так и общего [6; 13 и др.].

В современном электронном музыкальном инструментарии наиболее полно и совершенно воплотились веками накопленные информационные технологии в музыке и искусстве музицирования. Без знания технологических аспектов представлений о музыке, о музыкальном инструментарии (в том числе — музыкально-компьютерном) невозможна грамотная интерпретация музыкальных произведений исполнителем. Выдающийся пианист ХХ века И. Гофман пишет: «Когда учащийся-пианист вполне овладеет материальной стороной, то есть техникой, перед ним открывается безграничный простор — широкое поле художественной интерпретации. Здесь работа имеет преимущественно аналитический характер и требует, чтобы ум, дух и чувство, подкрепленные знаниями и эстетическим чутьем, образовали счастливый союз, позволяющий достигнуть ценных и достойных результатов» [24, с. 31-32].

Как показывает практика, информационные технологии в музыке существенно повлияли на способы передачи музыкальной информации. Мы живём в эпоху утверждения эры цифровой цивилизации, а вместе с тем - смены возможностей и средств обучения искусству, музыкальному искусству, в частности [13; 15]. В художественной сфере произошли кардинальные перемены, возникли новые творческие направления: «цифровые искусства» («digitalarts»), «дистанционное чтение» («distantreading») «цифровое чтение» («digitalreading», термин Ф.Моретти), «музыкально-компьютерные технологии», «медиаобразование», «цифровые гуманитарные науки» («digital humanities»), требующие совместных исследований гуманитариев и специалистов в области цифровых технологий.

Гуманитарные науки (humanities) в общем виде (с точки зрения их предмета) можно определить как изучение различных форм фиксации человеческого опыта, digital humanities (согласно исследованиям Л. Никифоровой) представляют собой способ существования гуманитарных наук в эпоху цифровых технологий хранения и трансляции информации, синтезируя различные направления исследовательской и практической деятельности. Digital humanities (DH) связаны с новыми формами накопления и трансляции знания, организации академического сообщества, образовательной среды. Современность называют новой информационной эпохой в истории человечества, постписьменной (М. Маклюэн), пост-печатной (Р. Дарнтон). DH – это исследование особенностей новой эпохи, социокультурных последствий цифровых технологий, критический анализ их возможностей и ограничений. «Исследовательская и проектная деятельность в области DH позиционируется принципиально как междисициплинарная и коллективная. Образовательный формат DH предполагает формирование новых моделей мышления на основе синтеза информационных технологий и достижений гуманитарных наук». Digital humanities- это также новый «формат художественного творчества, просветительства, работы с культурным наследием: «digital art», новые медиа, создание цифровых библиотек, архивов, баз данных культурного наследия и музейных коллекций, цифровые реконструкции, требующие совместных усилий гуманитариев и специалистов по цифровым технологиям. И связанные с этими процессами вопросы авторского права, интеллектуальной собственности. Digital humanities не отменяют традиционного ландшафта гуманитарных наук, но надстраиваются над ним».

Цифровая цивилизация также внесла глубокие изменения в область практического применения музыкальной письменности, не только в звукотворчестве, но и в сфере музыкального обучения и воспитания. Так, не без полемического оттенка, В. Мартынов в своей лекции «Музыка и письмо» [28]отмечает, что если еще совсем недавно, «до начала ХХ в. единственным способом хранения и передачи информации был текст, партитура или клавир, в любом случае это был текст», то «в начале ХХ в. с изобретением фонографа, звукозаписи все резко меняется У нотопечатания появляется конкурент, новая индустрия».

В современном музыковедении и в особенности музыкальной педагогике Запада (в частности, в США, поскольку в этой стране представлены, нередко в смешанной форме, многие музыкальные культуры мира) все чаще высказываются мысли о необходимости замещения традиционного нотного письма другими, альтернативными видами передачи музыкальной информации. Существует немало музыкальных течений и школ, ставящих под сомнение использование традиционной музыкальной письменности; сторонники этой точки зрения аргументируют свою позицию, основываясь на факте первичности именно «горячего» восприятия и воспроизведения музыки. По их мнению, письменная нотация не в состоянии передать все тонкости музыкального произведения и может только «испортить» музыкальные мысли «неевропейских» композиций, ибо «все идет со слуха, тут не может быть письменных вторжений» [28].

Превалирование слухового опыта, опирающегося на звучание, непосредственное впечатление - покорное следование слуховому образцу, отсутствие возможности зрительного осмысления и критического анализа текстовых источников музыкальной информации особенно ярко выразилось в музыкально-педагогических разработках некоторых систем массового обучения музыке в конце XIX – начале XX века. Работа с музыкальным текстом выкристаллизовалась как профессиональная дисциплина для музыкальной элиты - музыкальных школ, училищ и вузов. Понимание традиции работы с музыкальным текстом как элитарного вида музыкального образования укрепило свои позиции и доминирует во многих странах мира.

Высокотехнологичная информационная образовательная среда требует поиска новых подходов и принципиально новых систем обучения. Инновационная музыкальная педагогика на современном этапе связана с применением МКТ — современного и эффективного средства повышения качества обучения музыкальному искусству на всех уровнях образовательного процесса. МКТ являются также незаменимым инструментом образовательного процесса для различных социальных групп в приобщении к высокохудожественной музыкальной культуре, а также уникальной технологией для реализации инклюзивного педагогического процесса при обучении людей с ограниченными возможностями здоровья [8; 9; 14].

Внедрение МКТ в образовательный процесс позволяет актуализировать новые возможности подготовки и переподготовки высококвалифицированных специалистов различных уровней, востребованных в современном обществе, а также раскрывает новые перспективы в художественном образовании и музыкальной педагогике. Пути реализации концепции музыкально-компьютерного педагогического образования, позволяющие качественно изменить уровень подготовки педагога-музыканта на различных этапах обучения, сформировать необходимый уровень его информационной компетенции, обоснованы в ряде научных и научно-педагогических исследований [10; 11; 21 и др.].

Список литературы:

1. Горбунова И.Б. Высокотехнологичная информационная среда и музыкальное образование / Новые образовательные стратегии в современном информационном пространстве: Сб. науч. трудов. - СПб.: Изд-во «Лема», 2011. С. 97 – 101.

2. Горбунова И.Б. Информационные технологии в музыке. Т. 1: Архитектоника музыкального звука: Учебное пособие. – СПб.: Изд-во РГПУ им. А. И. Герцена, 2009. – 175 с.

3. Горбунова И.Б. Информационные технологии в музыке. Т. 2: Музыкальные синтезаторы: Учебное пособие. – СПб.: Изд-во РГПУ им. А. И. Герцена, 2010. – 205 с.

4. Горбунова И.Б. Информационные технологии в музыке. Т. 3: Музыкальный компьютер: Учебное пособие. – СПб.: Изд-во РГПУ им. А.И. Герцена, 2011. – 412 с.

5. Горбунова И.Б. Информационные технологии в современном музыкальном образовании // Современное музыкальное образование - 2011. Материалы межд. научно-практич. конф. / Под общ. ред. И.Б. Горбуновой. - СПб.: Изд-во РГПУ им. А.И. Герцена, 2011. С. 30 – 34.

6. Горбунова И.Б. Информационные технологии в художественном образовании / Философия коммуникации: интеллектуальные сети и современные информационно-коммуникативные технологии: Научное издание / под ред. д-ра филос. наук, проф. С.В. Клягина, д-ра филос. наук, проф. О.В. Шипуновой. - СПб.: Изд-во Политехн. ун –та, 2013. С. 192-202.

7. Горбунова И.Б. Музыкальный компьютер: Монография. – СПб.: Изд-во «СМИО Пресс», 2007. – 399 с.

8. Горбунова И.Б. Музыкально-компьютерные технологии в общем и профессиональном музыкальном образовании //

Современное музыкальное образование - 2004: Материалы межд. научно-практич. конф. – СПб.: ИПЦ СПГУТД, 2004. – С. 52-55.

9. Горбунова И.Б. Музыкально-компьютерные технологии в системе современного музыкального воспитания и образования // В сборнике: Педагогика и психология, культура и искусство. Материалы VII Межд. научно-практич. конф. "Педагогика и психология, культура и искусство: проблемы общего и специального гуманитарного образования". Казань: изд-во «Отечество», 2013. Вып. VII. С. 7-12.

10. Горбунова И.Б. Музыкально-компьютерные технологии как новая образовательная творческая среда // Актуальные вопросы современного университетского образования: Материалы XI Российско-американской научно-практ. конф. 13–15 мая 2008 г. – СПб.: Изд-во РГПУ им. А.И. Герцена, 2008. – С. 163-167.

11. Горбунова И.Б. Музыкально-компьютерные технологии - новая образовательная творческая среда // Universum: Вестник Герценовского университета. 2007. № 1. – С. 47-51.

12. Горбунова И.Б. Музыкальный звук: Монография. – СПб.: Издательство «Союз», 2006. – 164 с.

13. Горбунова И.Б. Новые художественные миры // Музыка в школе, 2010. № 4. С. 11-14

14. Горбунова И.Б. Феномен музыкально-компьютерных технологий как новая образовательная творческая среда // Известия РГПУ им. А. И. Герцена. 2004. № 4 (9). – С. 123 – 138.

15. Горбунова И.Б. Эра информационных технологий в музыкально-творческом пространстве. ХII Санкт-Петербургская международная конференция «Региональная информатика – 2010» («РИ – 2010»), Санкт-Петербург, 20–22 октября 2010 г.: Труды конф. \ СПОИСУ. – СПб., 2010. С. 232-233.

16. Горбунова И.Б., Заливадный М.С. Информационные технологии в музыке. Т. 4: Музыка, математика, информатика: Учебное пособие. – СПб.: Изд-во РГПУ им. А.И. Герцена, 2013. – 180 с.

17. Горбунова И.Б., Заливадный М.С. О математических методах в исследовании музыки и подготовке музыкантов // Проблемы музыкальной науки. 2013. № 1(12). – С. 272-276.

18. Горбунова И.Б., Заливадный М.С. Музыкально-теоретические воззрения Леонарда Эйлера: актуальное значение и перспективы // Вестник Ленинградского государственного университета имени А.С. Пушкина, 2012. № 4 (Т. 2). – С. 164-172.

19. Горбунова И.Б., Заливадный М.С. Музыка, математика, информатика: некоторые педагогические проблемы современного этапа // Современное музыкальное образование – 2013: Материалы межд. научно-практич. конф. – СПб.: Изд-во РГПУ им. А.И. Герцена, 2014. С. 22-26.

20. Горбунова И.Б., Заливадный М.С. Опыт математического представления музыкально-логических закономерностей в книге Я. Ксенакиса «Формализованная музыка» // Общество. Среда. Развитие, 2012. № 4(25). – С. 135-139.

21. Горбунова И.Б., Камерис А. Концепция музыкально-компьютерного образования в подготовке педагога-музыканта: Монография. - СПб.: Изд-во РГПУ им. А.И. Герцена, 2011. – 115 c.

22. Горбунова И.Б., Чибирёв С.В. Музыкально-компьютерные технологии: к проблеме моделирования процесса музыкального творчества: Монография. – СПб.: Изд-во РГПУ им. А.И. Герцена, 2012. – 160 с.

23. Горбунова И.Б., Чибирёв С.В. Компьютерное моделирование процесса музыкального творчества // Известия РГПУ им. А. И. Герцена. 2014. № 168. – С. 123 – 138.

24. Гофман И. Фортепианная игра. Ответы на вопросы о фортепианной игре / пер. с англ. Г.А. Павловой. – М.: Музгиз, 1961. – 224 с.

25. Заливадный М.С. Применение закономерностей слухо-зрительных синестезий в композиции и анализе музыки // Синестезия: содружество чувств и синтез искусств. Материалы межд. научно-практич. конф. - Казань: КГТУ, 2008. С. 156 –159.

26. Курт Э. Основы линеарного контрапункта / пер. с нем. З.В. Эвальд. - М.: Музгиз, 1931. 304 с.

27. Маклюэн М. URL: https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Маклюэн,_Маршалл

28. Мартынов В.И. URL:http://polit.ru/article/2007/10/05/martynov/

29. Танеев С. И. Подвижной контрапункт строгого письма. М.: Музгиз, 1959. 383 c.

30. Эйлер Л. Опыт новой теории музыки, ясно изложенной в соответствии с непреложными принципами гармонии / пер. с лат. Н.А. Алмазовой. - СПб.: «Нестор-История», 2007. 273 с.

31. Osgood Ch., Suci J., Tannenbaum P. The Measurement of Meaning. Urbana, Illinois: Illinois University Press, 1957. 350 p.

32. Schillinger J. The Schillinger System of Musical Composition. V. 1 – 2. New York: Carl Fischer, 1946. 1640 p.

33. Stockhausen K. Musik und Graphik //Stockhausen K. Texte. Bd. 1. Köln: DuMont Schauberg, 1992. S. 180 – 188.

Вестник Орловского государственного университета. Сер.: Новые гуманитарные исследования. Федеральный научно-практический журнал, 2014. № 4 (39)

Интерактивные сетевые технологии обучения музыке в Школе цифрового века:«Soft Way to Mozart»

УДК 378.02:372.8 Горбунова И.Б., Хайнер Е.

Интерактивные сетевые технологии обучения музыке в Школе цифрового века: программа «Soft Way to Mozart»

Звучание музыки воспринимается человеком как особое информационное пространство, являющееся одной из граней постижения духовной содержательности мира, его красоты, находящей отражение в звучании. Аудиальность восприятия музыкальной ткани связана с живым, непосредственным опытом человека, основанном на временнóй природе слухового переживания. Очевидно, что развитие музыкального слуха и музыкального мышления сталкивается с рядом проблем. Поэтому одна из основных задач музыкознания сегодня – осмысление на новом уровне функций музыки и как искусства, и как письменного языка, осознание современной культуры и культурных процессов, влияние информационных технологий на формирование творческой личности, способной осознанно воспринимать различные музыкальные явления и непосредственно, и аналитически, структурно. Исследования в области музыкознания, опирающиеся на ряд междисциплинарных связей (философия, эстетика, психология, акустика, нейрология, семиотика и др.) направлены сегодня, с одной стороны, на изучение культуры, веками сформировавшейся в истории человечества, с другой, – на изучение специфики современного восприятия музыки.

В музыкальной практике большое распространение приобрел новый класс музыкальных инструментов, куда входят клавишные синтезаторы, рабочие станции, мультимедийные компьютеры и др. Построенные на основе цифровых технологий инструменты отличаются значительными выразительными ресурсами, что открывает широкие перспективы их применения в музыкальном образовании [3; 5]. Новые возможноости позволили осуществлять с помощью таких инструментов не только звукозаписывающие, но и исполнительские задачи. Не случайно с развитием МКТ именно этот – аудиальный – опыт стал фундаментом для многих разработок дидактического направления. Создание музыкальных композиций с использованием новых возможностей музыкально-компьютерных технологий (МКТ) уже широко вошло в практику профессиональных композиторов. Пути реализации концепции музыкально-компьютерного педагогического образования, позволяющие качественно изменить уровень подготовки педагога-музыканта на различных этапах обучения, обоснованы в ряде научных и научно-педагогических исследований [7; 10 и др.].

Комплексная инновационная образовательная система «Музыкально-компьютерные технологии в подготовке педагога-музыканта», разработанная в учебно-методической лаборатории «Музыкально-компьютерные технологии» Российского государственного педагогического университета им. А.И. Герцена, опирающаяся на лучшие традиции отечественного классического музыкального образования, а также инновационный зарубежный опыт и современные МКТ, развивающая как собственно музыкальное, так и информационно-технологическое образование, не может не затронуть проблемы музыкальной письменности и социальных аспектов процесса информатизации художественного образования в целом [2; 8 и др]. Принципы, положенные в основу создания методической системы, являются базовыми для формирования новой предметной области в музыкально-педагогическом образовании, возможность появления которой обусловлена не только возникновением и развитием МКТ, но и сохранением откристаллизовавшихся письменных традиций музыкальной культуры. Их существование является фундаментом для сформировавшихся на современном этапе видов профессиональной деятельности не только музыкантов, работающих с МКТ (звукорежиссёров, саунд-дизайнеров, саунд-продюссеров, исполнителей на синтезаторах и MIDI-инструментах и др.), не только программистов — разработчиков в области электронных музыкальных систем, но и музыкальных педагогов, для которых современные технологии открывают новые возможности в решении дидактических задач [4; 6; 9 и др. ].

В программном обеспечении профессиональной деятельности современного музыканта и возможностях современного электронного музыкального инструментария наиболее полно и совершенно воплотились веками накопленные ИТ в музыке и искусстве музицирования. Формируется понимание того факта, что специализированный музыкальный компьютер становится новым многофункциональным политембральным инструментом музыканта. Музыкальному компьютеру, электронному музыкальному синтезатору и различным аспектам их функционирования в современной художественно-творческой среде посвящены работы (см., например, [4; 8 и др.] ).

Авторы статьи видят одну из основных задач педагогического исследования в том, чтобы раскрыть дидактические особенности использования МКТ, возможности их применения в музыкальном воспитании и образовании подрастающего поколения на основе классической музыки, традиционных подходов к способам трансляции многовековой музыкальной культуры. Важно, чтобы увлечение внешними, новыми, цифровыми эффектами и возможностями способствовало не только получению ярких и красочных «горячих» впечатлений в общении с музыкальным искусством [11], но и развивало критическое мышление, работало на развитие интеллектуального и культурного роста учащихся. Опираясь на исследования отечественных и зарубежных учёных, выделим научные работы А. Аракеловой, в которых рассматривается «в широком историческом контексте единство закономерностей функционирования музыкального искусства и образования в их взаимосвязи с государственной политикой, нормативно-правовым обеспечением и социокультурными тенденциями» [1, с. 4]. Отмечается также, что многие отечественные исследователи «вовсе не касались насущных проблем обеспечения всего комплекса необходимых условий для реализации тех или иных полезных инициатив. Кроме того, организационно-правовые и материальные факторы реализации образовательных программ, содержания и методов обучения-воспитания музыкантов никогда не исследовались с позиции музыкознания, что должно в наибольшей мере определять подход к функционированию музыкального образования как основы развития музыкального искусства и культуры общества» [там же, с. 5].

Сегодня становится совершенно очевидным тот факт, что в использовании МКТ таятся большие возможности для сочинения, исполнения, исследования музыки и музыкального образования и воспитания; что этого процесса не следует опасаться, а, напротив, нужно поддерживать и принимать в нём активное участие. Так, на часто звучащий вопрос: «Для чего нужно заменять одарённых музыкантов «машинами», отводить живое искусство на какой-то последний план и тем самым понижать эстетическую ценность музыкального искусства?» композитор и музыковед, педагог и учёный Ю.Н. Рагс, работавший в различных областях науки о музыке (среди которых: проблемы музыкальной эстетики, музыкальной акустики, исследования в области музыкальной психологии, взаимодействие композиторского и исполнительского творчества, исследование роли и места информационных технологий в музыке и музыкальном образовании, роль электронной и компьютерной музыки в современном музыкально–художественном пространстве и др.), отвечал: «Но в таком плане задачу никто не ставит. Известно, что компьютерное и электронное звучание заполняет уже сейчас рекламу, клипы, телевизионные и радиопередачи, кинофильмы и т.п. Их качество нас далеко не всегда удовлетворяет. Поэтому возникает необходимость готовить в этой сфере настоящих профессионалов, которые могли бы действительно поднять художественный уровень искусства. И учебные заведения должны не отходить от дела, а, по возможности, руководить им» [16, с. 202]. Призывая к объединению музыкантов, музыковедческих теорий, знаний о музыке, Рагс говорит и о необходимости объединения самих музыкантов: «Объединить по интересам музыкантов, работающих в общеобразовательных школах и в специальных музыкальных учебных заведениях по всем специальностям и на всех ступенях обучения (в ДМШ, училище или колледже, вузе)» и «использовать богатые возможности новых ИТ и в деле методического развития системы музыкального образования» [15, с. 65, 67], установить взаимопонимание между представителями различных направлений музыкально-научных исследований.

Нам бы хотелось подчеркнуть, что сегодня информационные технологии – это мощнейший образовательный и воспитательный ресурс. С помощью Интернета можно обменяться мнениями, общаться с людьми из любой страны, в любой точке планеты. Но мы еще не используем многие новые инструментальные возможности цифрового века в музыкальном образовании, среди них - преимущества интерактивного диалога с музыкальным компьютером для развития и совершенствования музыкальных навыков, применимых в повседневной академической практике.

Приведём результаты проведённого нами педагогического исследования, направленного на изучение возможностей использования как аудиальных, так и визуальных особенностей восприятия учащимися музыкального текста в сфере общего музыкального образования на примере интерактивной обучающей системы «Soft Way to Mozart», разработанной Е. Хайнер в 2002 г. и апробированной в музыкальных школах и студиях 52-х стран мира. Наряду с такими интерактивными образовательными программами, как «Музыка в цифровом пространстве», «Музыка и информатика», «Мурзилка. Затерянная мелодия», «Скоро в школу. Развиваем музыкальные способности», «Играем с музыкой П.И. Чайковского. Щелкунчик», «Играем с музыкой Моцарта. Волшебная флейта», «Алиса и Времена года», «Clifford. Угадай мелодию», «Музыкальный класс. Играй и учись», Ear Master School, Ear Power, Sight-Singing Trainer и др., программа «Soft Way to Mozart» также использует широчайший спектр медийных возможностей, ставя во главу угла фундаментальные принципы и научные достижения именно Русской Школы Музыки [17].

Особенностью системы «Soft Way to Mozart» является то, что она активно внедряется именно в музыкально-текстовое поле (индивидуальные навыки работы, прежде всего с музыкальным текстом), позволяя интегрировать непосредственный аудиальный опыт с возможностью «отстраненного» анализа музыкальной нотации. Это позволяет обогатить художественное образование и воспитание обучаемых, способствует их духовно нравственному развитию, позволяет активно внедрять способствующие здоровьесберегающие образовательные технологии в совокупности с принципами высочайших образовательных стандартов. По сравнению с другими школами мира, такими как Судзуки, Ямаха, Английская королевская школа музыки, Harmony Road, Kindermusik, методические школы Бастьена, Альфреда, Файберс и др., только Русская Школа Музыки базируется на разработанной и апробированной веками академической основе. Большинство вышеперчисленных школ и методических систем не основаны на академических принципы преподавания сольфеджио, которое только в условиях Русской Школы Музыки является краеугольным камнем музыкального и культурного развития начинающих (постепенное, непрерывное и системное развитие конкретных навыков, таких, как написание музыкальные диктантов, слышание и считывание музыкального текста, транспонирование, основы гармонии и прикладной музыкальной теории и др.).

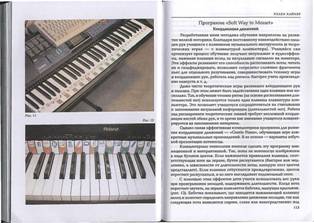

Центральной частью системы «Soft Way to Mozart» является специализированное программное обеспечение, необходимое условие функционирования которого – связь с цифровым клавишным музыкальным инструментом, осуществляемая посредством MIDI-интерфейса.

Выбор именно клавишного инструмента – клавира, синтезатора, MIDI -контроллера или фортепиано (в системе «Soft Way to Mozart» мы используем цифровые клавишные инструменты) был обусловлен откристализовавшимися традициями классического музыкального образования. Именно клавир способен передать многоголосную палитру музыкальной ткани наиболее точно. Клавишные инструменты в течение нескольких последних столетий являются своего рода звуковым эквивалентом многоголосного звучащего пространства. Многие жанры музыкальной культуры, основанные на использовании партитур, переведены в формат клавира для более широкого применения в исследовании музыкального материала и обучении ему.

Важнейшей особенностью МКТ является возможность непосредственного и одновременного взаимодействия не только всех мультимедийных структур, но и алгоритма взаимодействия этих структур с восприятием человека. Цифровые медийные технологии подняли процесс как визуального, так и аудиального восприятия музыкального потока на новый уровень: уровень высокой степени взаимодействия. Интеграция «горячего», непосредственного переживания с «холодным», аналитическим стала возможной благодаря тому, что «живое» время и опыт работы в «живом времени» стало единицей управляемой, а не стихийной, как это было ранее. В условиях системы «Soft Way to Mozart» человек может быть в поле «живого времени» и вне его путем нажатия клавиши синтезатора. Это позволило обогатить опыт аудиального восприятия возможностями визуального анализа, а также переосмысления разученного материала и оценки его с помощью встроенного статистический анализа.

Возможности педагогики, откристаллизовавшиеся в повседневной музыкальной педагогической практике - регистрация звуковых и ритмических погрешностей, метрическая и координационная стабильность, скорость зрительной, тактильной и аудиторной реакции при общении с музыкальным текстом – были изначально учтены в разработке системы «Soft Way to Mozart». Апробированные медийные средства, присущие МКТ (компьютерная графика, звуковая и графическая карты, анимация, интерактивные способы общения и др.) также нашли свое место в этой компьютерно-дидактической системе. Выбор клавира как части медийной системы МКТ обусловлен также визуальным тождеством, существующим между клавишным и нотным пространством.

Для реализации рассмотренных ранее принципов обучения была разработана программа повышения квалификации «Интерактивные сетевые технологии обучения музыке (программа «Soft Way to Mozart»)» для системы дополнительного профессионального образования преподавателей музыкальных дисциплин ДМШ и ДШИ и учителей музыки общеобразовательных школ. Одна из основных задач обучения по данной программе – определение уровня понимания роли МКТ и мультимедийного цифрового инструментария в обучении навыкам игры на клавишных инструментах, развитии слуха и чтения с листа. Тематический план программы повышения квалификации включает изучение следующих тем:

1. Природа музыкальных способностей человека. Роль мотивации в обучении музыке и интерактивные сетевые технологии обучения музыке. МКТ. Анализ различных школ мира с точки зрения подхода к обучению музыке. Роль Русской Школы Музыки в мировом музыкальном образовании. Интерактивность как фундамент мотивации в обучении. Особенности когнитивных функций человека. Роль когнитивного запроса в развитии знаний, умений и навыков.

2. Основные принципы построения курса обучения «Soft Way to Mozart». Нейропсихологические и физиологические особенности развития человека в процессе обучения музыке. Роль голоса в обучении музыке. Применение вокальной природы музыки в развитии слуха и голоса с помощью системы «Soft Way to Mozart». Развитие «музыкального зрения». Особенности зрительного восприятия музыкального текста и пути совершенствования «чтения» музыки с помощью системы «Soft Way to Mozart». Статистический анализ развития навыков с помощью системы измерения «Soft Way to Mozart». Музыка и лингвистика.

3. Основные составляющие интерактивной системы обучения «Soft Way to Mozart». Составляющие системы «Soft Way to Mozart»: специализированное программное обеспечение, взаимосвязь компьютера и синтезатора. Особенности применения системы «Soft Way to Mozart» в различных условиях и с различными группами обучаемых.

Преподаватели, успешно освоившие программу, овладели компетенциями, включающими в себя способность (и готовность): применять интерактивные сетевые технологии обучения музыке в учебной деятельности; разрабатывать учебные и презентационные материалы для проведения занятий с использованием МКТ и интерактивных сетевых технологий обучения музыке; вести занятия, используя современные МКТ и интерактивные сетевые технологии обучения музыке; владеть навыками обучения музыке людей с ограниченными возможностями на основе использования МКТ и интерактивных сетевых технологий обучения музыке; уметь создавать максимально эффективную среду для развития музыкальных и творческих способностей детей; способность применять современные методики и технологии организации и реализации образовательного процесса на различных образовательных ступенях в различных образовательных учреждениях (ПК-1); способность разрабатывать и реализовывать просветительские программы в целях популяризации научных знаний и культурных традиций (ПК-19); способность формировать художественно-культурную среду (ПК-21) и др.; а также "способность и готовность применять рациональные методы поиска, отбора, систематизации и использования информации; ориентирования в выпускаемой специальной учебно-методической литературе по профилю подготовки и смежным вопросам, анализировать различные методические системы и формулировать собственные принципы и методы обучения (ПК-28)"[13];«готовностью применять современные методики и технологии, методы диагностирования достижений обучающихся для обеспечения качества учебно-воспитательного процесса (ПК-13)» [14].

В процессе обучения была выявлена необходимость того, чтобы преподаватели:

знали многоаспектность и многокомпонентость понятий «интерактивные сетевые технологии обучения музыке» и «музыкально-компьютерные технологии» в контексте современного образования; методологические, психолого-педагогические, организационные и технологические аспекты использования интерактивных сетевых технологий обучения музыке и МКТ в современном образовательном процессе; возможности применении интерактивных сетевых технологий обучения музыке и МКТ в области художественно-эстетического образования детей.

умели определять проблемы, связанные с достижением нового качества образования, и предлагать способы их решения в опоре на современные интерактивные сетевые технологии обучения музыке и МКТ; анализировать и критически оценивать особенности развития образовательных систем в условиях функционирования высокотехнологичной информационной образовательной среды; разрабатывать модели образовательной деятельности в опоре на современные интерактивные сетевые технологии обучения музыке и МКТ;

владели: индивидуальными и групповыми технологиями работы с использованием интерактивных сетевых технологий обучения музыке и МКТ в современном образовательном процессе; приемами использования возможностей интерактивных сетевых технологий обучения музыке и МКТ для обеспечения качества управления образовательным процессом; технологиями интерактивного обучения музыке в сетевом пространстве, формами организация виртуальных классов, курсов обучения, конкурсов, академических концертов в онлайновом режиме; способами представления результатов деятельности в опоре на современные интерактивные сетевые технологии обучения музыке и МКТ.

В 2013-2014 учебном году на базе учебно-методической лаборатории «Музыкально-компьютерные технологии» РГПУ им. А.И. Герцена были проведены курсы повышения квалификации для преподавателей ДМШ и ДШИ, а также реализованы элементы дистанционного сопровождения по программе повышения квалификации «Интерактивные сетевые технологии обучения музыке (программа “Soft Way to Mozart”». Также в УМЛ «Музыкально-компьютерные технологии» было организовано обучение музыке на основе образовательной системы «Soft Way to Mozart» для студентов различных (немузыкальных) факультетов РГПУ им. А.И. Герцена в рамках проведения педагогического эксперимента при подготовке магистерской диссертации на тему: «Информационная образовательная среда как фактор формирования общекультурных компетенций студентов средствами МКТ» (магистерская программа «Информационные технологии в образовании», реализуемая на факультете информационных технологий РГПУ им. А.И. Герцена). Специализированное программное обеспечение было инсталлировано при поддержке Ресурсного центра Управления информатизации РГПУ им. А.И. Герцена. В работе со студентами и педагогами были использованы зрительные, зрительно-анимационные и другие интерактивные модификации, разработанные для системы «Soft Way to Mozart».

Использование МКТ и программы «Soft Way to Mozart» способствовало широкому развитию интереса к осознанному прочтению и исполнению фортепианной музыки у 100% студентов РГПУ им. А.И. Герцена, принявших участие в пилотировании системы. Все участники научились играть на фортепиано двумя руками по нотам и наизусть музыкальные произведения в условиях групповых занятий от 5 до 10 человек (с одним преподавателем). Большинство студентов (91%) успешно исполнили выученные произведения на акустическом фортепиано, продемонстрировав высокий уровень самооценки и уверенности в собственных силах. Большинство участников справилось с разучиванием пьес начальных классов ДМШ и приступило к разбору более сложных произведений (98%). Выбор визуальной презентации нотного письма основывался на личном выборе, связанном с предварительным опытом каждого студента и варьировался: некоторые выбрали оригинальную нотацию (54%), другие – упрощенную буквенную(46%).

Занятия с группой преподавателей ДМШ показало, что программа «Soft Way to Mozart» воспринимается педагогами-профессионалами как мультимедийная система, потенциально способная обогатить палитру занятий, обусловленных школьной программой. Знакомство с основными принципами системы «Soft Way to Mozart» вызвало понимание системы как традиционного, но модифицированного подхода в обучении ключевым навыкам игры на инструменте, чтения нот с листа, запоминания музыкальных произведений на более технологичном, интерактивном уровне.

Результаты педагогического исследования были представлены также на:

XII Международной ежегодной научно-практической конференции «Современное музыкальное образование – 2013», проводимой совместно РГПУ им. А.И. Герцена и Санкт-Петербургской государственной консерваторией им. Н.А. Римского-Корсакова (декабрь 2013 г.);

Международном семинаре-практикуме «Музыкально-компьютерные технологии в Школе цифрового века», проведённом на базе УМЛ «Музыкально-компьютерные технологии» (март 2014 г.);

Ежегодной внутривузовской научно-практической конференции «Непрерывное педагогическое образование в современном мире: от исследовательского поиска к продуктивным решениям. Реализация образовательных программ в образовательной среде вуза» в РГПУ им. А.И. Герцена (март 2014 г.);

Международной научно-практической конференции «Высокотехнологичная информационная образовательная среда» (апрель 2014 г.).

Участники семинара «Музыкально-компьютерные технологии в Школе цифрового века» - преподаватели музыкальных академий и педагоги музыкальных школ из России, Польши, Беларуси, Казахстана, Израиля, Испании, Коста-Рики, США, Турции - отметили, что МКТ и система «Soft Way to Mozart» работает в различных странах мира и на разных континентах одинаково эффективно. Дети увлечены разбором музыкальных произведений, они соревнуются в том, кто и сколько прочтет пьес при наименьшем количестве ошибок; оказывается не нужным фальшивый искусственный фантастический мир (вспомним тот бум, который вызывали в свое время компьютерные игрушки типа ‘Guitar Hero’ и ‘Garage Band’во всем мире, когда дети часами совершенствовали навыки игры на искусственном, специально сделанном только для такой игры, инструменте); музыкальное искусство является неисчерпаемым источником настоящих сокровищ, которые действительно обогащают каждого ребенка. Любовь к музыке и желание уметь играть самим на музыкальных инструментах у детей не только сохранились, но и усилились благодаря проведенным занятиям.

Педагоги отметили также, что музыканты должны учить детей играть Моцарта и Баха на «настоящей» клавиатуре и с помощью» настоящего» нотного текста; если чтение музыкального текста и игра на музыкальных инструментах станут популярными и повсеместными, то из широкой массы любителей обязательно откристаллизуется достаточно многочисленный контингент одаренных детей, и специалисты в музыкальных и общеобразовательных школах получат больше времени для того, чтобы воспитывать талантливых слушателей с развитым музыкальным мышлением, способных к творческому саморазвитию, посещающих филармонии, концертные залы и театры.

На примере системы «Soft Way to Mozart» оказалось возможным проследить, как МКТ способны интегрировать устоявшиеся доцифровые психологические модальности с новыми мультимедийными возможностями. Новые мультимедийные модули в режиме живого времени легко интегрируются с процессуальной природой музыкального языка и позволяют представить музыкальную нотацию в новом, динамическом качестве. Непосредственное восприятие музыкального потока сочетается с аналитическим, что в значительной мере усиливает дидактические возможности и переводит познавательный опыт обучающихся на качественно новый уровень развития. Синтез МКТ и модифицированной музыкальной нотации открывает новые дидактические возможности в использовании нотной записи, актуализации её использования в условиях цифрового века. Цифровое обогащение нотного письма с использованием системы «Soft Way to Mozart» может содействовать решению ряда проблем музыкального образования XXI в. и способствовать новому этапу развития музыки как одной из важнейших граней постижения мира.

Многогранность, глобальная применимость МКТ дают новые, по сути, безграничные возможности самореализации, стимулируют стремительное развитие интеллекта, поднимая обучение на новый уровень; совместимость с традиционными музыкальными технологиями создает условия для преемственности музыкальных эпох и стилей, их взаимопроникновения и синтеза, укрепляя интерес к музыкальной культуре в целом.

Результаты использования системы за сравнительно короткий промежуток времени показали, что медийное использование МКТ в сфере подачи аудиального и зрительного материала в совокупности с возможностью непосредственного взаимодействия с музыкальным текстом на тактильном уровне является тем путем, благодаря которому возможна интеграция «горячего» – непосредственного и «холодного» – аналитического опыта человека.

Музыка развивает мозг человека, и ничто так не содействует развитию творческих способностей, как желание петь, исполнять музыкальные произведения и непосредственное умение играть на музыкальном инструменте. Авторам статьи представляется, что сейчас, когда мир переживает очередной экономический и политический кризис, именно музыкальная культура, музыкальное образование, опирающееся на высокую духовность, толерантность, межкультурную коммуникацию, способно повлиять на уровень общественного сознания, поддерживать и развивать контакты между специалистами в различных областях знаний и классическим музыкальным искусством (см., например, [12]).

Возможности МКТ, обусловленные функционированием высокотехнологичной информационной образовательной среды, благоприятствуют, как никогда ранее, объединению людей различных стран и континентов, обогащению и усилению процессов сохранения и развития многовековых традиций музыкальной культуры в педагогической практике.

Авторы выражают благодарность Михаилу Сергеевичу Заливадному за ценные замечания и полезные советы, высказанные при подготовке статьи к публикации.

Список литературы:

1. Аракелова А.О. Отечественное образование в области музыкального искусства: исторический опыт, проблемы и пути развития: Автореф. дисс. ... д-ра искусствоведения. – Магнитогорск, 2012. 50 с.

2. Воронов А.М., Горбунова И.Б., Камерис А., Романенко М.Ю. Музыкально-компьютерные технологии в Школе цифрового века // Вестник Иркутского государственного технического университета: Научный журнал, 2013. № 5(76). С. 256-261.

3. Горбунова И.Б. Информационные технологии в музыке. Т. 2: Музыкальные синтезаторы: Учебное пособие. – СПб.: Изд-во РГПУ им. А. И. Герцена, 2010. – 205 с.

4. Горбунова И.Б. Информационные технологии в музыке. Т. 3: Музыкальный компьютер: Учебное пособие. – СПб.: Изд-во РГПУ им. А.И. Герцена, 2011. 412 с.

5. Горбунова И.Б. Информационные технологии в современном музыкальном образовании // Современное музыкальное образование - 2011. Материалы межд. научно-практич. конф. / Под общ. ред. И.Б. Горбуновой – СПб.: Изд-во РГПУ им. А.И. Герцена, 2011. – С. 30 – 34.

6. Горбунова И.Б. Музыкальный компьютер: Монография. – СПб.: Изд-во «СМИО Пресс», 2007. – 399 с.

7. Горбунова И.Б. Музыкально-компьютерные технологии в общем и профессиональном музыкальном образовании //

Современное музыкальное образование - 2004: Материалы межд. научно-практич. конф. – СПб.: ИПЦ СПГУТД, 2004. – С. 52-55.

8. Горбунова И.Б. Музыкально-компьютерные технологии как новая образовательная творческая среда // Актуальные вопросы современного университетского образования: Материалы XI Российско-американской научно-практ. конф. 13–15 мая 2008 г. – СПб.: Изд-во РГПУ им. А.И. Герцена, 2008. – С. 163-167.

9. Горбунова И.Б. Музыкально-компьютерные технологии - новая образовательная творческая среда // Universum: Вестник Герценовского университета. 2007. № 1. – С.47-51.

10. Горбунова И.Б., Камерис А. Концепция музыкально-компьютерного образования в подготовке педагога-музыканта: Монография. - СПб.: Изд-во РГПУ им. А.И. Герцена, 2011. – 115 c.

11. Маклюэн М.URL: https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Маклюэн,_Маршалл

12. Одинец В.П. О Борисе Захаровиче Вулихе – потомственном математике и типичном петербуржце (К 100-летию со дня рождения) // Вестник Сыктывкарского университета, 2013 . Сер.1. Вып.17. – С.123-128.

13. Приказ Министерства образования и науки РФ №1464 от 06.04.2012 г. «Об утверждении и введении в действие ФГОС ВПО по напр. подготовки 073100 Музыкально-инструментальное искусство (квалификация (степень) «бакалавр»)»

14. Приказ Министерства образования и науки РФ от 17 января 2011 г. N 46 «Об утверждении и введении в действие ФГОС ВПО по напр. подготовки 050100 Педагогическое образование (квалификация (степень) "бакалавр")»

15. Рагс Ю.Н. О сайте «Трибуна музыканта-педагога» // Современное музыкальное образование - 2004: Материалы межд. научно-практ. конф. (26-29 октября 2004 г.). Ч. I. - СПб.: ИПЦ СПГУТД, 2004. – С. 64 – 67.

16. Рагс Ю.Н. Перспективы развития курса информатики в музыкальных образовательных учреждениях // Современное музыкальное образование - 2003: Материалы межд. научно-практич. конф. (9-11 октября 2003 г.) – СПб.: Изд-во РГПУ им. А.И. Герцена, 2003. – С. 200 – 203.

17. URL: www.softmozart.com / www.softmozart.ru

Источник: Вестник Орловского государственного университета. Сер.: Новые гуманитарные исследования. Федеральный научно-практический журнал, 2014. № 4 (39).

The Impact of Vision on Learning Musical Notation

|

|

by Hellene Hiner

Because you go to a gym and use a stationary bicycle for cardiac exercise, does it mean that you can ride a real bike? Of course not! Because riding a bicycle involves a complex set of skills. You do not learn how to balance on a stationary bicycle, yet this is a missing but necessary link in training to ride a real one.

What would happen if you try to ride a real bike after training on a stationary bike? If you are an athletic type with a good sense of balance and coordination, it is less likely that you would be afraid of getting hurt if you fall off. Someone less skilled, however, could be afraid of falling, or fearful of even trying.

This is exactly what has happened for many centuries with piano learning, because there is a missing but necessary link in music education, just as there is in the example of training for a race on a stationary bike. This link is the visual perception of score and keys.

Learning a complex set of skills requires that all the components be developed together from the very start to build a strong, unified network. Losing any of the separate parts of the network, even for a short time, complicates the learning process for many students, except perhaps the most structured players.

Piano playing is about the relationship between the piano keys and musical notes – with plenty of looking and little actual seeing.

What is the difference between looking and seeing? For a moment, imagine yourself for the first time looking at a sheet of piano music and knowing that it is in a language that you do not know. Or imagine yourself standing in someone else’s kitchen looking for the saltshaker among all the spices on the shelf, but you are unable to see what the hostess could find with closed eyes. When a student of any age first stares at the piano keys and a music score, he/she is blind in the same way you would be looking for the salt among all the spices on the shelf. When a person cannot see, he/she needs to develop the skill to see, not the textbook knowledge about how to see things. Most piano students are constrained by music education that keeps them blind. Many well-known schools try to deal with problem of music blindness differently, but all the approaches have the same foundation – bondage on muscle memory. This is exactly how we teach blind people. How do the blind learn? They learn by touch. They also need assistance.

Russian music educators deal with blindness by endlessly playing scales and finger exercises and studies. Method books creators all over the world deal with blindness by offering 'hand position' curriculum, when hands and fingers are fastened to certain keys. Some schools have declared that reading music is not necessary at the beginning, and that playing “by ear” is a more fruitful approach. Some schools present beginners' sheets with finger numbers. Some inventors create systems of training muscles by blindly chasing lit keys or moving colorful objects on a monitor screen.

Some inventors use interactive computer programs to try to teach the eyes the knowledge of what they need to see.

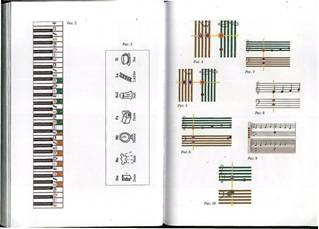

These methods are like the stationary bicycle! They all overlook one important component of the complex skill to play piano: visual/spatial integration. Therefore, if we want to make piano lessons more effective, our duty is to let people SEE the music notes and their relationship to the piano keys from the very first steps.

How to do it? It is not as hard as one might think! I can be accomplished in the same way that we do it in day-to-day life. When we deal with something that we have trouble seeing, we MARK it, underline it, or we add highlights and labels! This helps our eyes to see. But it is not enough to use colorful markers and color music notes. We have to do it in a logical and organized way, in a way that makes sense for our students! When we classify similar looking things, we have to consider their outstanding features in order to add visual support for eyesight. Look at shelves of spices in grocery stores! There are hundreds of the same looking jars, but they are organized in a way to help our eyes to get what we want: each jar has a name on it, a picture of the spice and they are placed in alphabetical order.

Many kids are capable of learning letters before they even go to school, because people created brightly marked alphabet letters for them. Remember, how we teach children with cards or blocks? Each letter is presented in large print with pictures and colors that help children to see the connection between the abstract letter, picture and phonetic pronunciation. For example, kids see a picture of an apple, say 'apple' and figure out the letter A!

The same strategy could be used with music notes! But when we chose, for example, 12 different colors for 12 different piano keys we miss the whole point of visual support in learning. Can these 12 colors add to the fact that 12 different keys have 12 different sounds? Not really. They simply add confusion.

Each music note has outstanding features. We have to determine all of them and make them obvious for the beginner's eyesight.

Each music note has outstanding features.

- If spaces and lines are the same tracks, why don't we present them with the same width on elementary level? Kids won't think, that white track is a 'break between lines' any more!

- If music notes are all either on spaces or on lines, why don't we color them in two contrast colors for beginners eyes to instantly catch the difference?

- If Treble and Base Clefs are mostly for different hands, the best way to present them –is to give them different colors, too, but colors of let's say, a tree. It would help to explain gradual changes in pitch – from dark to light, from trunk to crown.

If music notes go up and down and corresponding keys – right and left, why don't we turn the Grand Staff sideways in elementary presentation to line notes with keys and to help beginners to SEE a straight link between them right away?

If music notes go up and down and corresponding keys – right and left, why don't we turn the Grand Staff sideways in elementary presentation to line notes with keys and to help beginners to SEE a straight link between them right away?

If music notes have only seven names for all the keys and sounds, why don't we place a label of these names on each note and a key? This way a beginner will SEE the relationship easily, not struggle looking for information.

If music notes have only seven names for all the keys and sounds, why don't we place a label of these names on each note and a key? This way a beginner will SEE the relationship easily, not struggle looking for information.

- If it is so hard to shift eyesight along all lines and spaces, why don't we use computer interactivity to support focus at the elementary stage and then moderately develop its ability to shift?

Many teachers and many parents are afraid to give beginners too much support, because they think that they'll become dependant upon them. But street signs didn't ever spoil any driver, especially when an area is unfamiliar and the road is shrouded by fog. Don't you remember your own frustration that the signs were too small and blurry, when you badly needed to see where to go? But we never even look at the signs, once we know way.

Today is a time to decide whether we give our students a better tool to see music notes and piano keys and to learn effectively - or to keep them in darkness just because we learned by a different method. For many former piano students it is so obvious what should be done! But this a is very difficult decision to make for major music educational institutions, music publishers and music teachers. There is a lot of money already invested in method books and music sheets, all which attempt to explain to eyes what they ought to see and present the traditional Grand Staff from the very start. The major question here: in whose best interests do we have to decide – in the interest of people who have personal/financial reasons to maintain the status quo, or in the best interest of our kids?

By continuing music lessons in 'blind mode' millions of parents not only waste a lot of money in very slow and ineffective ways of teaching piano, they invest in ways of teaching music that could completely change their kids lives for the worse… by introducing frustration and failure at an early age.

How to teach Solfegio in XXI century

|

|

|

|

|

|

This article was published in a book for educators How to Teach Solfeggio in the 21st Century by Moscow State Conservatory in 2006.

“Soft Way to Mozart” ®

"Without music life would be a mistake" – Frederich Nitsche

The language of music is an international one, but its elements are not available to most people. Common methods of teaching music are in desperate need of reform. In the era of science and technology, less and less interest is being paid to advanced forms of music and music education. Technological progress calls for a progressive approach to music education that can both regenerate this interest and make it universal. This article is dedicated to the above mentioned ideas and to reformed ways of teaching music through computer technology.

Some ideas regarding social and historical preconditions of total musical ignorance

Throughout history, music education has been failing to reach the majority of people. Musical illiteracy, the inability to read and write music, has plagued human society for centuries. However, until recently, regard for music skills such as mastery of a music instrument or control and clarity of singing voice was generally very high.

Nevertheless during these “golden” centuries of the development of the professional branch of music education, music pedagogy was not the most popular subject when learning music. In scoffing at students’ lack of talent and their dilettante attitudes, music professionals beat the hands of their negligent pupils. These rigid methods of music pedagogy focused on raising “new geniuses” and disregarding amateurs. Even well known composers in their memoirs have expressed irritation against the “hard of hearing” dilettanti they had had to teach to earn their living. There was no other reward in their teaching.

Remember one of the “Small Tragedies” by Alexander Pushkin – “Mozart and Salieri.” There is a scene in which Mozart brings home a fiddler and asks him to perform “something by Mozart.” Salieri is indignant at the sight of such “mockery of an object of worship.” This is a very indicative scene in which keen Pushkin’s eye noticed the difference between genius’s and artisan’s attitudes towards the problem of dilettantism in music.

From today’s perspective that scene has a deeper more elaborate meaning.

The point is not only that Mozart was tolerant of the fiddler’s mistakes, but also that he had a wise attitude to music in general. One needs to be a genius in order to understand that a music composition is alive only while it is being performed, even if imperfectly.

Until the emergence of adequate sound-recording devices, human society needed gifted, bright performers, and as a rule there was no lack of listeners. Therefore, most of the music schools in Europe and later all over the world concentrated on training future virtuosos.

Music pedagogy, preoccupied with the problems of improving performers’ techniques, created entrance contests that were to eliminate the “hard of hearing” ones; it was not particularly interested in universal competence in music. Because of the methods of teaching students to play instruments, reading and writing music were so difficult for ordinary people that they would give it up early and join the army of ignorant dilettanti. As to gifted learners, they stood the test of the first steps in music not because of the existing systems of initial training but in spite of them.

This can be the very explanation for such a great amount of nonsense, mistakes and bad habits that have remained in music pedagogy until now.

The neglectful attitude to the vocal nature of music language is accepted in countries with a literal system of naming music notes. Music pedagogy in general is not able or willing to develop a student’s ear for music and the singing voice of people who do not possess a marked music aptitude (in spite of discoveries in this field made by some well-known pedagogues who could teach even hard of hearing persons to sing clearly). Music schools have a tendency to turn any beginner into a performing artist. Often there is no tolerance for mistakes and imperfect playing even at the very beginning of music studies.

All these drawbacks apply to both pro-western countries where the government does not support music education and the countries of the former socialist block where professional music training is supported by the state.

However, it should be mentioned that while in Russia and the other republics of the former USSR music schools, colleges and conservatories aimed only at perfecting professionals, at the same time there was a wide net of public music schools easily accessible and affordable to everyone. These circumstances contributed to more wide-spread music education than in countries with a capitalist system. Thus not only exceptionally gifted learners but also children with average music aptitude could attend music schools in the former USSR. In addition, the number of classes a child had in his/her schedule at a music school gave a much better chance of building a better foundation for music development. This, in turn, encouraged professionals to keep searching for new methods to improve the initial stages of music education. Gradually some of these attempts resulted in music classes being introduced into education programs of regular schools.

However, the division of music education into general (as a part of general education) and specialized (music schools and studios) as well as a selective approach to enrollment for music school did not encourage music pedagogy to create methods that would be aimed at teaching each child how to read music. Although there are certain advantages to the Russian system of music education with its time-proven structure and methodology, even Russian music education has not managed to overcome the problem of overall musical illiteracy.

With technical progress, extracting music sounds by means of pressing the “Play” button on a record player or a tape-recorder has quenched people’s thirst for enriching their own lives with music. At the same time, their common musical ignorance has raised the demand for producing music that meets a lower level of expectation. New standards were established in society as Chuck Berry succinctly his hit “Roll over, Beethoven!” when he said, “If they can’t teach us, then we can do without it.” At the present time, this is the gist of the general public’s attitude toward music education. Now a new generation of music performers and “composers” has appeared on stage. Despite not being able to read or write music, these musicians are gaining popularity.

This is the reason why today interest in studying music in the USA is much lower than the popularity of sports or martial arts. The profession of a piano teacher is one of the least secure partly due to the high drop-out rate. According to the statistics printed in a Houston newspaper, publishing houses that issue materials for piano classes (materials designed for several years of studies), sell 100 books for the first-year learners vs. 10 books for the second year and only one book for the third.

Any US federal or state program has rarely subsidized education for those studying professional piano and other music instruments. The low effectiveness and high cost (an average American cannot afford more than one individual lesson per week) bring about a further loss of interest in the subject. At schools, kindergartens or nursery care centers as well as in households of common Americans, one can hardly meet people who are able to play the piano or especially read music.

Children in Russia also have little possibility to learn the language of music during the lessons in non-music schools. Outdated methods of training at music schools make the majority of graduates only partially literate with added the aggravation of feeling extremely negative toward playing music for the rest of their lives.

As a result, both approaches to music education (self- or government-supported) still end up dividing society into a small stratum of talented professionals and the musically ignorant masses who are not even able to appreciate the skills of the former.

Thus, the essence of the problem is not just in the structure of financial support for music education but also in the lack of effectiveness of its methods. We will be able to save music only by the means of highly effective systems of teaching music at public schools and free access to knowledge for any child, no matter how musically gifted. Furthermore, the survival of language of music in the world depends on that drastic measure.

However, human society is still strongly and dangerously convinced that music competence is available only for the talented. And therefore, the problem of universal music education is assumed not to be very urgent or vital. Somehow we don’t see a connection between empty philharmonic halls and packed stadiums with a frightening spiritual ignorance in most people.

Similarly, we fail to notice the causal relationship between teenage violence, drugs, and depression and music has a primitive connection with all human beings, so we shouldn't ignore its power

Even when people understand the catastrophic situation in music education, their efforts to “save music” are very often in vain. For instance, the progressive community of the USA shows sincere concern for the state of music. Institutions, funds and associations are founded with the main aim of “saving music.” However, the salvation of music in the opinion of these funds and societies consists of purchasing music instruments, manuals and notes. Most of the people running these organizations believe that all methods of music education have already invented been and do not need any revision.

However, there are no universal methods that will teach everyone (independent of their talents) to read and write music, so the resources to save music are spent without many results. The salvation of music is out of the question without reforming music education, without close to universal music competence. The art of music can be saved and supported only by an army of competent listeners who have a highly developed music memory, ear and thinking, and who can read and write music texts.

Is it possible to love a language passionately without understanding it?

We often ask the question, “Is music education really necessary for people without music talent?”

Music in our opinion adds another dimension to our lives. This is a language that can connect people of different cultures and backgrounds, a language that opens up new horizons for everyone using it. This language becomes a great part of our life; it forms our consciousness and ideology. Recent research at the University of California, Irvine, conducted by now deceased Gordon Shaw has scientifically proven that music and piano studies develop the human brain and, above all, spatial and temporal reasoning.

Psychological discoveries have also verified a fact that is more incredible: there are no people deprived of an ear for music. And it is only natural. A child is exposed to the language of music, like the spoken one, even while still in his/her mother’s belly. Human speech has a music component – intonation. A newborn baby responds first of all to the intonation (the music part) of speech and only much later he/she begins to comprehend the meaning of words. It is natural to conclude that a child begins to understand the language of music much earlier than spoken language. Plato once said: “Music training is a more potent instrument than any other, because rhythm and harmony find their way into the inward places of the soul.” Why should we deprive anyone of the greatest tool in developing one’s soul and mind?

Where do the people who sing out of tune come from?

Scientists of the Moscow State University guided by A. N. Leontiev along with English scholars have discovered an interesting fact. There are two main mechanisms of sound perception: tonal perception – which basically allows us to differentiate between sound pitch— and timbre perception which lets us determine a sound’s timbre. (More information can be found at http://yurpsy.by.ru/biblio/leontev/25.htm Leontiev, A. N. Lectures on general psychology. Moscow, 2000. Lection 25. Pitch hearing.)

Leontiev’s team tested a non-musician audience on its perception of two sounds of the same frequency but different timbre. For the English-speaking audience, they used “u” as in “boot” and long “ee” as in “beet.” Amazingly, 30% of people could always answered that “u” is a lower sound even though in reality it was sometimes an octave higher that the corresponding “ee.” They took the tone-deaf group and made them do simple exercises on tonal perception then continued experiment. For 10-15 minutes a day that group practiced vocalizing a given sound produced by an electric device (in order to take the timbre out of the picture). The outcome of the experiment was sensational – previously tone-deaf group showed highly significant improvement. That led to a hypothesis about the way our perception is developed. Early on, most of the interaction a child is involved in comes through speech. Perception that is being developed is mostly timbre based, rather than tone-based, particularly in Indo-European languages. The development of the tone-differentiating apparatus is very minimal. This is also supported by the fact that individuals from cultures whose languages use tone modulations in their speech (like Chinese Mandarin) have a better ability for tone recognition.